The Learning Loop

EXPERIENCE ≠ TIME

An unfortunate truth has revealed itself: I have hit an age when people – prospective clients, students, new acquaintances – assume I have “experience.” It doesn’t seem that long ago I had the opposite problem; establishing credibility in the early stages of a new professional relationship required effort, a clear demonstration of competency. I should welcome this development, but my vanity gets in the way! And vanity has got me asking: what is experience anyway? Is it measurable in years? What does experience mean to a career-hopper who hasn’t spent much time doing any one thing?

Experience is Another Type of Learning

I contend that “experienced” is what we label someone who has been effective in gleaning lessons from life. In that sense, it’s just another type of learning, one that eschews classrooms, lectures and textbooks, in favor of waking up every day, getting out in the world, trying things, succeeding sometimes and failing often, and moving onto the next thing. This is experiential learning.

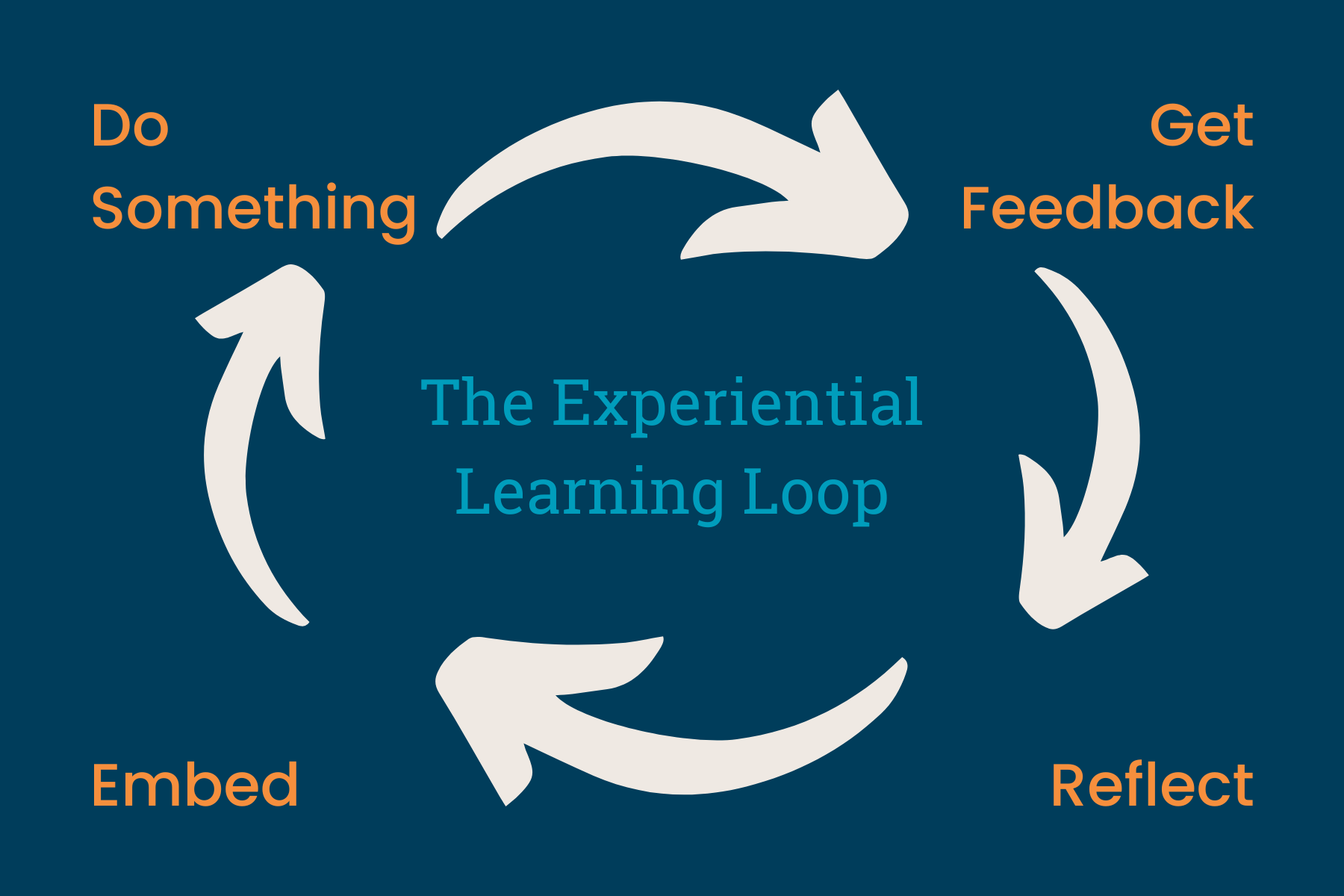

Experiential learning is different than school learning, but we’re never really taught how it works. That’s a shame since we spend so much time (potentially) doing it! There is no guarantee that being a successful student translates: school is relatively passive – show up in your PJs and listen to a professor speak, read the assigned material, do the assigned homework, cram information into your head for the exam – while experiential learning requires you to be in the driver’s seat. For that reason, arriving at a place where other’s call you experienced isn’t just about the passage of time, but about getting in, and staying in, the Experiential Learning Loop.

Figure 1. The Experiential Learning Loop represents the process by which we learn from real life exposure. It’s different than what we do in school, but nobody ever tells us that.

Experiential learning is comprised of four steps. Doing these steps over and over and over results in experience. They are:

Do something. To get in the experiential learning loop you must have … an experience. If you don’t do something, you have nothing to learn from or about. It’s amazing how many people can’t consistently make it this far.

Get feedback on the thing you did. How is it received? How does it compare to what others have done? What would have made it better or more effective?

Reflect on the feedback. Does it make sense to you? I previously wrote that feedback is a funhouse of mirrors; what comes back isn’t purely about you but also the shape of the mirror, so you need to figure out what to take and what to leave behind.

Embed the feedback. Put the feedback into practice to cement the learning and make it part of what you do (or even who you are).

While iterations through this loop may be correlated with time, time is not the only – and not even the most important – predictor of experience. That’s good news to young professionals and career changers: you can accelerate your accumulation of experience by paying attention to the Experiential Learning Loop.

Don’t Skip Steps

In some processes, you can skip a step and still get a pretty good result. I like peanut butter sandwiches even without the jelly. Socks are not always required. Flossing is optional even if my dentist tells me otherwise. You get the idea. Experiential learning is not one of those processes. Every step matters; if you don’t do them all, you don’t get the benefit.

Figure 2. Every step matters. Shortcuts create their own problems.

To be honest, I’m not sure Observers exist in the real world. Plenty of people skip the “do something,” but I don’t think many of them are in the habit of getting feedback, reflecting or embedding either. The other three, though, are people you run into every day.

Everyone loves positive feedback, but the other kind – euphemistically “constructive” or “developmental” – often hurts. To spare our sensitive selves, we might be inclined to skip directly to reflection, which in this case, is better described as self-reflection. Self-reflection is a good thing, but it shouldn’t be the only thing. Our own mirrors are warped and full of pockmarks, just like everyone else’s. If reflection relies exclusively on one mirror, we will never confront or resolve our blind spots.

If you skip reflecting – that is, the step where you internalize the feedback – and just blindly embed what you’re told, you’re simply taking orders. Order takers fail to generalize. They don’t learn about themselves, their habits, their biases and so can’t make any permanent adjustments to those things. They will always be dependent on someone else to direct them; they will always need to be managed. If you are failing to advance in your career, ask yourself honestly if you’re skipping the reflection.

Failure to embed a lesson you’ve understood, at first blush, is incomprehensible to me – isn’t the hard work already done!?! I’d like to think these people are as rare as Observers, but Mistake Repeaters are everywhere. They know what needs to be different and they understand why, but they just can’t bring themselves to do it. The reality is: embedding is hard work, too. Habits and routine are powerful beasts. Breaking out of them requires effort because they’re routine. They’re automatic. We don’t think about them when we do them, so understanding that they need to be different isn’t the lynchpin it might seem. We must reprogram ourselves. If we don’t, the efforts we made in the first three steps are moot.

Maximize Each Step

Once you’re making sure to take each step, you can also boost the pace of experiential learning by maximizing them. Here’s how:

Do Something

Do many somethings. Get busy and get active. The more you do, the more frequently you put yourself in the Learning Loop. Pretty obvious, right?

Do new somethings. Stretch yourself beyond what you’re already pretty good at. The shape of the learning curve is steep at the beginning, then plateaus. If you want to learn quickly, you need to stay at the steep part of the curve. That means doing things you haven’t done before.

Get Feedback

Choose feedback-rich environments. There are industries and cultures that put feedback at the center of what they do, that train people to give and receive feedback, that make delivering feedback central to the role of leadership. Consulting is one of those industries; McKinsey is one of those companies. If you select your environment wisely, you won’t be able to avoid feedback (sometimes, to your chagrin).

Ask for it. If you’re not in a feedback-oriented environment, you’re going to have to ask for feedback. You may even have to train the people around you to be comfortable giving it to you. If you love everything else about the space you’re in, this is worth the effort.

Learn to absorb informal feedback. No matter how good you get at asking for it, the volume of feedback that comes at you informally will always outweigh what you can get formally. A colleague misunderstood your point until someone else restated it for you; that’s feedback. Your boss glazed over one analysis, but engaged deeply on a second; that’s feedback. Your teenager is embarrassed by your outfit; that’s feedback (buried under a pile of sass, no doubt). Feedback is everywhere; teach yourself to see it.

Listen for what you don’t want to hear. Human brains, as an adaptive trick to deal with information overload, tend to strip out what doesn’t immediately resonate with us in favor of what does; it’s called confirmation bias. But when it comes to learning quickly and well, the feedback you don’t want to hear is often what you most need to hear. Those are the nuggets that contain the instructions for improvement; don’t let your brain discard them before you’ve even had a chance to consider them.

Reflect

Schedule it. Make reflection a habit, as routine as brushing your teeth. Thinking time looks and feels deceptively like idleness, so ambitious people often neglect it. But this is when creativity sparks, strategy is formulated, ideas are connected and understanding is built; the awesome results of thinking time make a strong case that it is far from idleness. Find a way to put it in your day. Some people journal regularly. Some people block their calendars. I am in the habit of using shower and driving time. Find something that works for you and stick with it.

Get to the bottom. To get the most of the feedback you’ve received, you have to make sense of it, to really understand it. Ask yourself not just what the feedback was, but why. Peel back the layers to get to the root. A deep understanding is requisite for real change.

Generalize. Define the very broadest application of your deeply-understood feedback. Does it just apply to meetings on financial performance with John Smith on Tuesday afternoons when you’re wearing a pink shirt? Or have you instead learned something about how to engage with colleagues on stressful topics? While the example is absurd, we all tend to read the narrowest definition into constructive feedback, but our learning is amplified when we’re willing to extend the scope of the lesson.

Embed

Iterate. Immediately apply the learning, ideally by redoing the exact thing you got the feedback on. Iteration is not only a great way to build strong work products; it also provides a powerful process for doing, learning and doing again. Nothing cements a developmental insight like putting it into practice.

Create new habits. There’s no greater “embedding” than turning your learning into a new habit, something so automatic you don’t even have to think about it anymore. Deliberate repetition, association of your new habit with clear events (“cues,” in the language of habit science) and immediate positive rewards are all ways to turn an action into a habit. (For a good read on the topic, check out James Clear’s book, Atomic Habits.)

As with most things, attentively engaging in experiential learning is bound to yield more fruit than passively doing so. Since this type of learning dominates our adult years, the bulk of our lives if we’re lucky, I’m convinced that mastering it is the secret to success. The process isn’t complicated: get in the Learning Loop, stay in it and extract maximum value from every step. Getting old may help others recognize your experience but you don’t have to actually be old to have it.