Loyalty in the Workplace

CORPORATIONS ABANDONED THEIR EMPLOYEES. IS IT ANY SURPRISE EMPLOYEES ARE NOW ABANDONING THEM?

Not long ago, I found myself unfulfilled and disillusioned in a traditional role at a Fortune 500 and decided to leave just two years into my tenure. It got back to me that the CEO’s reaction to my departure was to exclaim: “Well, she’s not loyal!” Another executive in the room - who subsequently relayed the conversation to me - countered that my loyalty was to ideas and principles, not an organization. I don’t believe she swayed his thinking at all, but the whole episode, in addition to cementing my reasons for departing, did get me thinking.

What does it mean to be loyal in the context of the workplace? Does the object of one’s loyalty have to be concrete - like people or the organization - or can it be more abstract? Is loyalty an inherent quality, something a person possesses, or is it entirely situational? Is it something to be given or something that must be earned? Above all, is it always good or does it, in large quantities, simply equate to obedience (which weak leaders may appreciate because it makes their jobs easier, but almost certainly isn’t going to lead to the best outcomes)?

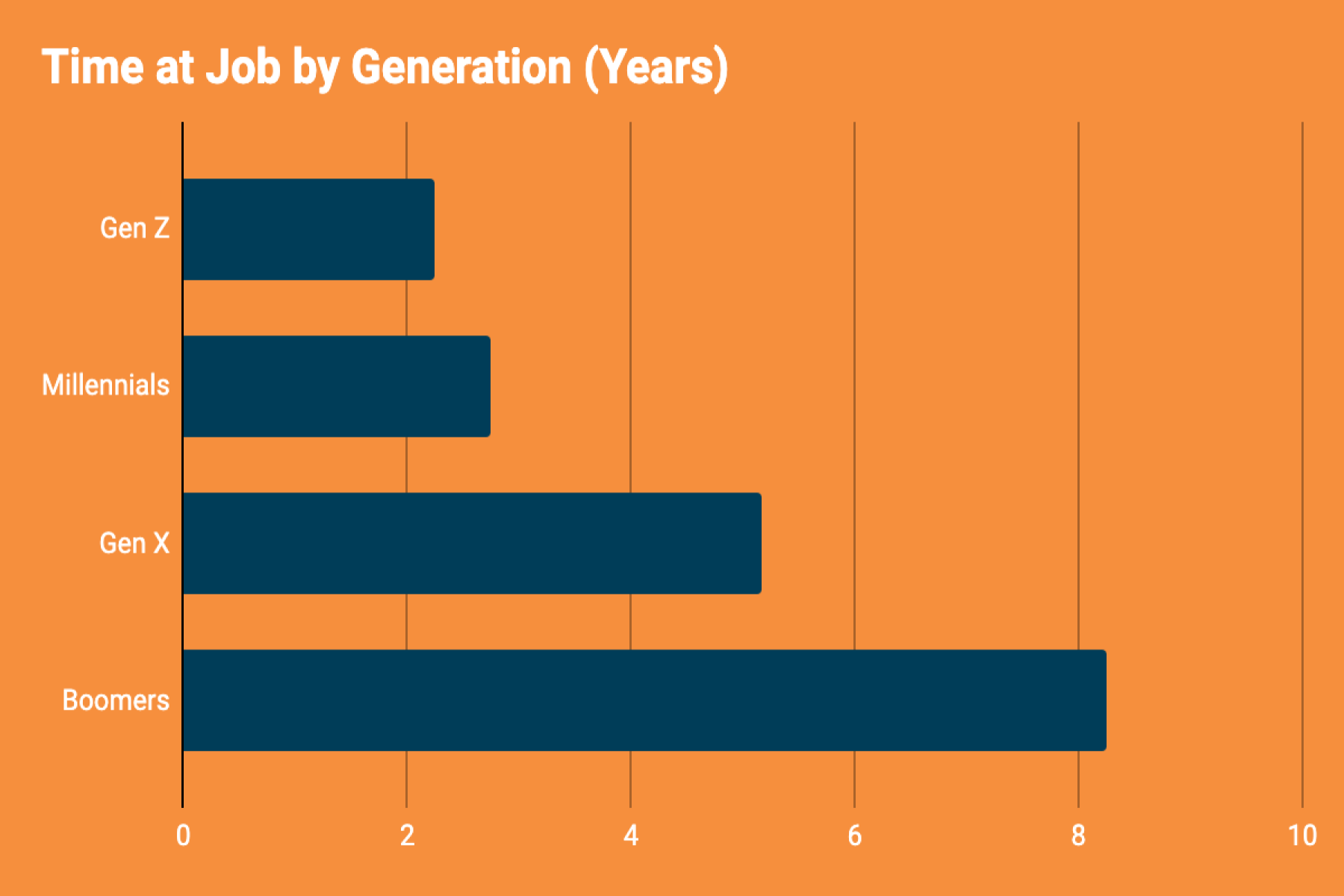

The meaning of loyalty in the workplace is particularly relevant now, during the Great Resignation, when ~48 million people quit in 2021. But it’s a shift that has been underway for decades as professional mobility has increased, the widespread entry of women into the workforce requires flexibility to accommodate the (ever uneven) burdens of parenting, and younger generations expect more fluidity in their careers (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1. Time in role decreases with every generation, with Millenials being labeled as the Job Hopping Generation.

It’s no surprise that this CEO, a white man on the verge of retiring, would have a very different perspective than me on the meaning of loyalty. I contend that his view is not only defunct, but dangerous for organizations and leaders that wish to compete in today’s talent market.

The Underpinnings of Loyalty: Biology, Psychology and Philosophy

Search for writings on loyalty and you will be quickly overwhelmed. It is a frequent topic in many fields - creative writing, business and marketing, psychology, psychiatry, sociology, religion, economics, political theory, philosophy and ethics, to name a few - and there isn’t widespread agreement or clarity. I make no claim to expertise here, but share my main learnings with heavy reliance on a wonderful (but dense - you can thank me in the comments for wading through it), well-sourced and recently updated entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

The Origin of Loyalty

Though there is disagreement as to the presence of a genetic basis for loyalty, there seems to be little dispute that there is a long-standing evolutionary basis for a level of “solidarity, faithfulness or allegiance to a group or individual” (Psychology Dictionary). We are inherently social creatures with a reliance on groups to bond, provide for our basic needs and raise the next generation through homo sapiens’ extended childhood and adolescence. Loyalty is the mechanism by which we stabilize these relationships for the long-term survival of humanity.

While the survival imperative underpinning loyalty has arguably diminished - we now have lots of structures that impersonally provide for our basic needs - it has not entirely disappeared. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown us that, even in modern times, we need others to survive, as social isolation increased the likelihood of early death by 26-32%. Still, the primary motivation for loyalty has shifted over millennia from a dominant focus on survival to one of flourishing. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia:

The deeper reason for thinking that … loyalty ought to be fostered and shown … resides in the conception of ourselves as social beings. … We are social creatures who are what we are because of our embeddedness in and ongoing involvement with relations and groups and communities of various kinds. Though these evolve over time, such social affiliations become part of who we are … [and] part of what we conceive a good life to be for us. Our loyal obligation to them arises out of the value that our association with them has for us.

While I find no consistent agreement about what loyalty actually is or even whether it is virtuous (more below), there appears to be no question that the total inability by an individual to display loyalty would be a defect. Given its outsized importance in evolution, survival and the successful navigation of our highly-integrated social world, it is quite rare to find someone entirely devoid of the capacity for loyalty. So, when we claim that someone is not loyal, we are likely omitting the most important bit: loyal to what?

Loyalty Requires a Target

There is also disagreement (sensing a theme here?) as to what types of entities may be the recipients of our loyalty, but there is some preference for limiting objects of loyalty to people, personal collectives (eg., families), quasi-persons (eg., organizations) and social groups. In this construct, devotion to ideals, principles and causes, would instead fall under the realm of integrity rather than loyalty.

Loyalty need not be exclusionary; that is, displays of loyalty don’t necessarily need to be against one entity in favor of another (though they can be). To illustrate, a mother can show loyalty to one child without displaying disloyalty to her others. Loyalty is, however, particular, in the sense that it is not universally owed. Contrast honesty, for example, which is a virtue we expect to be afforded to all of humanity. In fact, loyalty begins to lose its meaning if we try to apply it universally. This is further evidence of the foolishness in impugning an individual for their lack of loyalty in a single instance. There are many, many more entities to which we are not loyal than there are those to which we are. The more interesting question becomes not whether we are loyal, but why we choose the particular objects of our loyalty.

James Kane, author of Safer. Easier. Better: The True Nature of Human Connections, says that our brains seek trust, belonging, and purpose. He says providing those to people makes them loyal. More specifically, we tend to be loyal to::

Targets that reflect our identity, with which we have deep involvement. The target of our loyalty must be ours: my friends, my family, my country. In part, this explains our willingness to take risks or bear burdens on behalf of the object; we see our fates as intimately entwined.

Targets that mesh with the ideals, principles and causes for which we stand. While we previously rejected such abstractions as direct objects of our loyalty, they nonetheless factor prominently into our selection of more concrete targets.

Targets that exhibit mutualism, that need us as much as we need them and show loyalty in return.

A change in the target’s performance in any of these may be the cause for withdrawing a prior loyalty. This is not disloyalty, but a realistic reflection of the shifting relevance of social entities within our lives.

Loyalty is Rational

Loyalty may not be maximizing in the cost-benefit sense, but it is still thoughtful. As already discussed, loyalty is particular, so we need not enter into relationships that don’t serve us, complaisantly meet every demand placed upon us, or remain committed to previously loyal relationships, even those that initially seem chosen for us (eg., family, country). There is a term for a servile, unthinking form of loyalty - “blind loyalty” - and it is roundly criticized by all but the most authoritarian and cynical among us.

Rather, behaviors that characterize “thinking” loyalty would include:

Sacrifice of near-term individual benefits (or acceptance of near-term hardship) in exchange for or in support of long-term benefits, even if those benefits are ill-defined offshoots of group success.

Willingness to forego greater long-term benefits promised by another entity with which we do not identify in favor of “good enough” benefits from the one with which we do identify.

Sustained effort to change the object of loyalty for the better if it fails to live up to our standards, rather than abandon it immediately. This is brought to life in the concept of a “loyal opponent” and termed “giving voice” by social scientist Albert Hirschman.

If the object of our loyalty ceases to be “worthy or capable of being a source of associational satisfaction or identity-giving significance,” it is not disloyal to abandon that object, particularly if some effort has been made to encourage improvements that would return it to worthiness. The exact threshold at which this forfeiture is justified, however, is rarely agreed upon and is often the real source of accusations of disloyalty.

Loyalty is a Problematic Virtue

In fact, there is no universal agreement that loyalty is a virtue at all! The opponents of loyalty as a virtue most often pin their arguments on the frequency with which loyalty is used to drive unethical conduct. After all, “when an organization wants you to do right, it asks for your integrity; when it wants you to do wrong, it demands your loyalty.”

What’s clear is that the value of loyalty doesn’t stand alone; rather, it is sensitive to - even dependent upon - the value of its object. There are (and should be!) contingencies in the development of loyalty. Complaisant, servile, blind loyalty is a corruption of the concept; even in its mildest forms, it is one we should feel comfortable rejecting.

Workplace Loyalty Under Fire: Employers Have Only Themselves to Blame

When it comes to the application of loyalty to our professional lives, the most important takeaways so far are:

It is unlikely that an employee is inherently disloyal, especially if they’ve managed to successfully navigate into senior roles in your organization. Primary, secondary and graduate school, prior professional experiences, decades of living on this crowded planet have given them ample opportunity to develop the capacity for loyalty … and for truly anti-social behavior to be sussed out.

Loyalty is not and can not be owed everywhere; employers are no exception. We choose a finite set of objects for our loyalty based on our identity and belonging, alignment with our most closely-held ideals and the demonstrated capacity of the object to return loyalty in kind. Loyalty is given to the worthy.

It is not disloyal to forfeit obligations to an employer that is no longer worthy, particularly if the object makes no effort to respond to efforts to help it return to worthiness. (The exact moment I decided to leave the Fortune 500 featured in the story that kicks off this blog is when a very senior executive - one of two front-runners to be the next CEO, in fact - told me to “stop trying to change things.”)

Ethics and business results require us to reject a corrupted, blind version of loyalty, even when weak leaders demand it. It is far too easy to point to major corruptions like Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Anderson and more, where people who knew the truth contributed to grotesque, even criminal, behavior and failed to blow the whistle due to their blind loyalty.

In light of these truths about loyalty, it is not at all difficult to understand why the loyalty employers enjoy from their employees has been weakening with each generation.

Workplaces no longer consistently play a strong social role in our lives. Under Friedman’s influence, many employers abandoned the role they previously played in our communities in order to focus exclusively on shareholders. In abdicating their position as social organizations, they no longer qualify to even be considered as potential objects of our loyalty.

Workplaces occupy a diminishing role in our individual identity. The social vacuum employers left behind has been replaced, for the fortunate, by other centers of membership and identity. But far too many have been simply left with disillusionment (a gap which has, recently, come to be filled by authoritarian leaders commanding blind loyalty).

Workplaces are frequently disloyal to employees. Jack Welch was lionized for decades as a leading practitioner of a management approach that not only deprioritized employees but saw them as line items. They are cost centers to be slashed, reallocated, offshored as convenient to drive near-term profits. Employers have forgotten that loyalty is a two-way street.

When I first conceived of this blog, I initially wrote that the CEO’s definition of loyalty was outdated. But it’s not actually loyalty and its application that have changed. Instead, under the influence of Friedman’s thinking and the shortsighted, self-serving leadership of today’s retiring business leaders, employers have become unworthy objects of loyalty. Remaining leaders are beginning to ask questions, particularly as the pandemic unwittingly galvanized millions of disgruntled employees into action. My question is: will they do enough to regain the trust of employees, to again be worthy of the kind of loyalty they demand?

What has been your experience with loyalty in the workplace? Do you think today’s employers are owed loyalty? Are they worthy of it? Leave your thoughts in the comments and don’t forget to subscribe to learn about new blog posts!